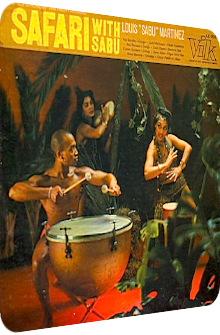

Sabu

Safari

1958

Many an Exotica artist invites the listener to a safari, if not with a dedicated album, then at least via a few thematic tracks spread around several LP’s. Since everyone can create playlists easier than ever, new overarching themes and schemes surface. Les Baxter’s African Jazz (1959) features an eponymous track, Martin Denny’s Afro-Desia (1959) focuses on a fantasy-based connection and distributes it over the whole album. And let’s not forget Exotica’s pinkest artifact ever, Edmond De Luca’s symphonic concept album and field trip Safari (1958). All these albums are coruscating, aglow with technicolor, full of prospering coppices and jungles. And now, enter Safari by conguero Louis “Sabu” Martinez (1930–1979).

Released in 1958 on the Vik label, its five unique compositions break the boundaries. Similar to his masterpiece Sorcery! (1958), Sabu forces the listener to face drum stampedes, bone-crushing rhythms and well-known instruments such as saxophones and vibes that sound unlike anything else. Safari steps out of the shadow of Latin and builds a fire. The bandleader is in good company and reigns over eight skilled men: drummers Evelio Quintero, Ray Baretto and Ray Romero, saxophonists Cecil Payne and Gene Allen, dedicated timbalist Steve Berrios, tromboner and vibraphonist Steve Hitchcock as well as bassist Oscar Pettiford. A mixed choir of African singers fuels the imagination further. These are not a Lion King’s euphonious patterns – this is one nocturnal ritual out in the steppes!

Oh my God, the timpani, the destructible oomph! Jeanette is the name of the coquette that opens the album in a less helical, more raucous fashion. Various drum patterns become intertwined, showcasing Sabu’s true focal point in the 50’s. Heterodyned female chants conflate with Gene Allen’s snake charmer oboe all the while Evelio Quintero’s and Ray Baretto’s tribal midtempo conga groove guide the lady into the most mephitic of all chlorotic illusions. The lead melody might invoke what one could rightfully call the Orient, but two counterparts are injected in order to lessen this impression: the wonderful conga base frame whose echoey haze evokes jungle hues, and then Cecil Payne’s baritone sax which might or might not function as a last artifact to the greenhouse jungle of one’s apartment at Lower East Side. These ingredients do not always harmonize well, but this twilight dichotomy is the cauterized point Sabu is trying to make.

The adjacent Dawn is a much shorter trip due to the runtime of less than four minutes and a revved up tempo resembling a proper tunnel vision. Sabu and his men beat their congas and evoke a fusillade of punctilios that is awesome, saltatory and even diaphanous due to the various cowbells and Steve Berrios’ serrated timbales. Mixed chants, an ophidian encore of Cecil Payne’s baritone saxophone and a constant viscid liveliness of the drums make this one heated area to be in. Ubas then rounds off side A with even faster rhythm patterns, true, but remains more tame and earthbound due to its Samba origin: Jack Hitchcock’s helicoidal vibraphone sparks would be splendid in a Crime Jazz title, the saxophone is somewhat normalized as well, and it is therefore up to the rolling drum cavalcade with the centered spectral chants to lure the devil out of purgatory.

Side B is reserved for two longform pieces Sabu is particularly known and loved for in the world of Exotica, and it is superfluous to describe the technical versatility and prowess of the heterodox segues, as they obviously have to be experienced to be believed. Rest assured that these pieces do not depict one’s lush jungle or steppe. This is serious business, with not a single doldrums, let alone a euphonious tone in sight. These things keep Sabu on top of his game though. The 12+ minutes of Nadenga feature the prominent double bass rivulets of Oscar Pettiford before the array of bellicose chants, sax paroxysms and polyrhythmic jungle drums is dropped yet again, mightily so. The plasticity in this long drum piece is gorgeous: once the listener has adjusted and adhered to the orderly state of the drums and finds them soothing or even beguiling, Sabu’s leading conga is beaten even harder, breaks out of the rhythm and functions as a melodious instrument itself, as crazy as this may sound. Despite the long runtime, Nadenga remains surprisingly focused, there are no ever-changing rhythm patterns and zero gimmicky inclusions. What you hear in the first two minutes is the basic recipe of this cesspool.

The same can be said about the eponymous finale Safari, a saffron aureole of ten and a half minutes. Supercharged with Gene Allen’s moon-dappled oboe gyrations, several mountainous mixed chants and comparatively laid-back drums that are undoubtedly sophisticated but still tame enough to not take over, Safari is the one track that really does focus on melodies. The rhythm thicket is wadded and prospers throughout the arrangement, but in lieu of tachycardia drums and sudden protrusions or convulsions, this is one streamlined endpoint… were it not for the increasingly silvery cymbal haze and timpani catenae. This is a savage album after all.

If you dig drums, even just a little bit, go for Sabu! But know what to expect: this is not your mellifluous afternoon extravaganza of harmonious Exotica tunes, no, Safari is a recondite, erupting volcano whose rough belligerent power hasn’t lost anything of its cataclysmic aurora. This doesn’t come as a surprise, for Sabu’s works of the 50’s are only mildly based on Latinisms; their rhythms only serve as frames. More important is the interplay of the textures. Smoke is in the air, riots are prepared, voices from the dark are called out time and again. How prosaic.

At the end of the day, Safari is a strikingly intimidating work. It is by no means frightening, but since it lacks cheap thrills and thundering shock effects, it gains momentum at the same time. The saxophone and vibraphone veils plus the fugacity of the oboe, however, are the only earthbound things to grasp. Everything else is in limbo, despite Safari being no Space-Age album. The drums are energetic but simultaneously superimposed and languorous, depending on the listener’s preferred volume. Turn it way up, and their staggering force makes for a life-like experience. Turn it down a notch, and you might enjoy the nuances and interstices. This is a Hollywood-esque work, but way too sophisticated for being pinpointed or linked to the glamour and vivacity of the primary coasts in the United States. This one feels real… or was that surreal?

Exotica Review 435: Sabu – Safari (1958). Originally published on May 30, 2015 at AmbientExotica.com.